The Evolution of the Artist’s Hand: Despina Konstantinides

In Conversation with Irene Archos

Despina Konstantinides’ landscapes are based less on her eye and more on her mind’s eye. Aflame with almost-neon-like yellow, orange, chartreuse in unexpected angles, the contours force the eye upwards and over almost in an electrically charged current. These are both real and surreal; they are realistic allegories of inner landscapes that reveal by what they conceal, by forcing the viewer to see deeply into forms they cannot take for granted. These landscapes call for the viewer to construct the meanings implicit in them, by digging deep and through the tones and values of their own truth. They are not generalized landscapes but unique manifestations of the “artist’s hand.” “Landscape is just an excuse to find form in painting, to find my hand in the painting and go through and beyond it,” Konstantinides explains. “It is in that act of painting that forces you to become inventive.”

I spoke long and deeply about the concept of the artist’s hand and finding it in a painting during my visit to her studio as part of LIC Arts Open Studios 2019, at Reis Studios, the artfully drawn building next to Silvercup Studios off 21st Street. LIC Arts Open Studios is an annual event allowing public access into the process of many professional artists centered in the Long Island City area. The concept of finding the artist’s hand was something she was introduced to by her painting professor in graduate school. “To find your hand in a painting,” Konstantinides explains, “is to push form and then push again, going even further, going beyond yourself.” It is the pushing against the self to go beyond the literal or everyday self to find the real self, in extension the same process that happens in a painting.

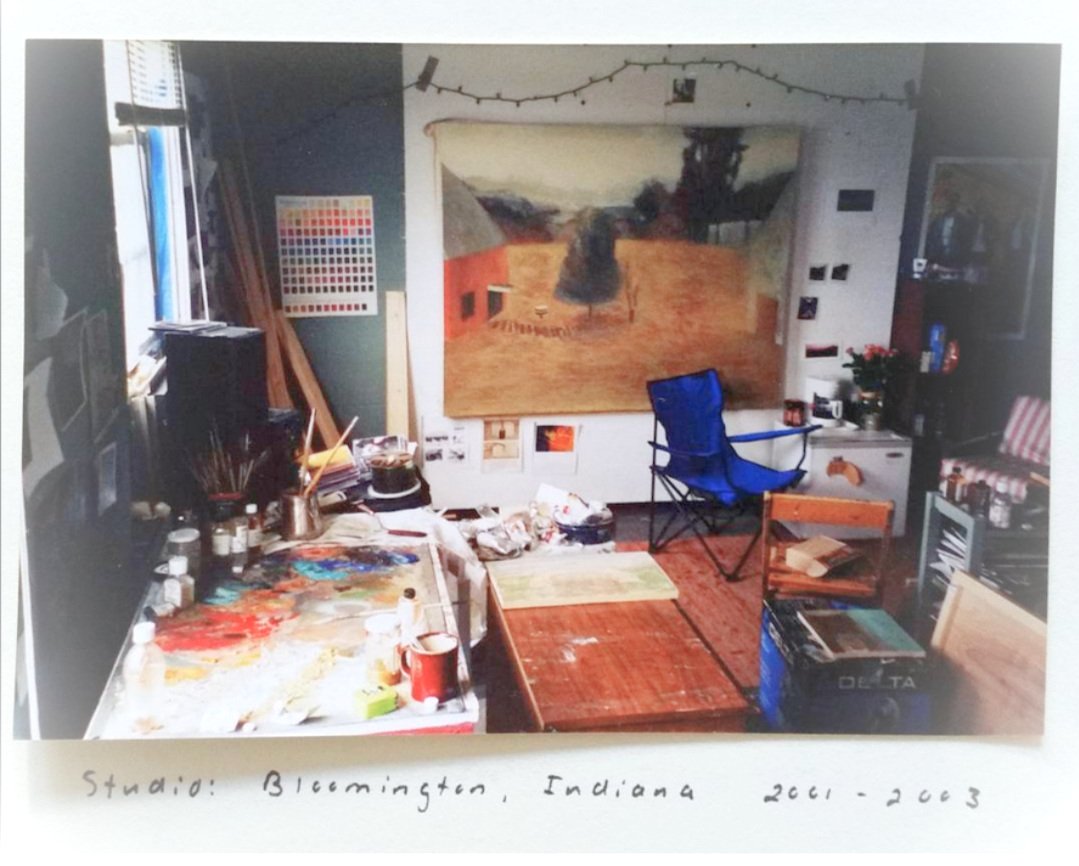

This enlightening idea was instilled in her by her graduate professor, Barry Gealt, who observed that her initial landscapes were general and lacked any specific signature. He pushed her to go from creating smaller life studies of 8X10” to creating in the large at least 5X5’. According to his logic, you could not hide in a large painting.

Finding her hand in her art has taken Despina many years. Her development as a painter is slow, methodical, contemplative and experimental. Her first painting was in 4th grade, an oil painting of a vase of flowers. Since then she has studied painting with Pratt in Venice, Burren College of Art in Ireland and Trinity College in Connecticut where she majored in philosophy.

Yet, the first painting where she actually found her hand was not until many years later in the second year of graduate school in a landscape scene outside of her studio window. Her career speaks to the truth that the process of becoming a painter mirrors the process of becoming yourself. She recalls how this awakening dawned on her when she walked into Benozzo Gozzoli's "La Capella dei Magi" in Florence.

“It was the first experience of art that went beyond the narrative, that made me understand what was happening between the lines,” she notes. “It gave me the overwhelming feeling of walking into the space and wanting to open up. It’s no different from what good musicians, or good designers or architects do—they change your relationship to yourself essentially because it provides a different access point to yourself.”

Another inner-eye opening lesson came from her love of Morandi. “Through Morandi I learned to understand what sincerity means in a painting,” she shares. It was the simple act of her professor, Richards Ruben, drawing a line in three ways that changed the course of her understanding of the process. He drew a light line, then a heavier line and then a third line, but this time with intention of sincerity. She saw the difference immediately. “There is something that happens on the picture plane when as a painter you actually mean it. If you are sincere, and fully present so that they painting becomes your world,” she says. It was the sense of sincerity and touch that she found in Morandi that she saught to replicate in her process. It was shortly after this developmental stage of studying Morandi that she was able to let go of the physical need to see a view but rely in her inner eye. It was this period that set off her most inventive stage: she took off paint using a palette knife; made tree limbs lighter instead of dark so the eye would be forced to work around it; included layering.

In the beginning of her career she hated landscapes but now they have become her signature theme. “I am addicted to landscapes. I love painting because it knows me better than I know myself. It is what keeps me coming back to it. “

Her Hellenic heritage while not explicitly present in her paintings is again present in her process through what she explains as orexi”. What I most love about Greek culture she states, is the orexi in the way they approach living. They are always saying Yes! And going forward with things. The appetite for creating new works and discovering herself has been strong for 30 years now.

It is the process that brings an artist’s deeper unfolding of self that is at the heart of her oeuvre. As her professor, Richards Ruben explained it, each person is the thinker of thoughts, there is a constant stream of talking in one’s head. But who receives those thoughts while you are talking to yourself? There is a listener within each thinker that receives those thoughts. It's like an inner echo. Art gets to the listener within each thinker.

“I still think of painting as existing in the space between the thinker and the listener between the everyday self and the more fundamental self,” she states, “This is the drive behind the painting. To find that inner self.”

To trace the process of her becoming, both as a painter and as a person, check out her website, www.despinapaintings.com